|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

|

Mortar bedding has provided a good, cost-effective means

of securing hip and ridge tiles onto single and double lap roof

coverings for centuries. But in the last 30 years we have seen the

introduction of more and more systems for constructing a roof without

using mortar bedding. In some instances the dry fix systems have

advantages over traditional mortar bedding, and sometimes it appears

that it has only been provided to fulfil the dry fix ethos of the

manufacturer.

Mortar bedded hip tiles, if undertaken correctly on a

domestic roof, have been proven to perform very well. If the mortar

bedding is not done correctly, then the result is a hip that can leak,

or tiles that can fly off in high winds.

Hip tiles are generally some of the last tiles to

go on and therefore some of the first to come off. On large buildings

like offices, schools, hospitals and shopping complexes, the roof

structures are generally lightweight, often involving steelwork trusses,

rather than the more traditional rigid timber structures.

The effect of longer spans and lightweight steel is

greater thermal movement and flexing of the structural elements,

resulting in a degree of movement at junctions like the hip. Therefore

it is essential to have a junction system that is not totally rigid, but

is still secure and weather-tight.

Security

With mortar bedded hips with single lap tiles, the total weight of the

hip tiles and mortar, during the wet stage, is taken by the hip iron at

the bottom. The load on the hip iron increases with the pitch of the

roof (the steeper the pitch the more the load), the length of the hip

(the longer the hip the more the load), and the surface finish of the

roof covering (resin slates and polymer coated FC slates being the worst

as there is little adhesion between the mortar and the surface of the

roof covering). Once the mortar has adhered to both the hip tiles and

the roof covering then the hip iron is doing less work, until the

bedding mortar cracks and the hip tries to slide down the roof.

With dry fix hip systems each individual hip tile

should be secured through to the undertray, or better still through the

undertray into the hip rafter or hip batten. Provided each hip tile is

securely fixed to the roof structure directly or indirectly, then wind

uplift loads can be resisted. However, as each hip tile rests on an

undertray and there is no mortar bedding, there is still the risk of the

hip tiles sliding down the hip line.

Where each individual hip

tile is screwed through into the hip rafter, or a hip batten, as gravity

pulls on the screw fixing, so the screw bends and pulls the hip tile in

harder to the roof surface. Provided the screw fixing is tight to begin

with, the degree of slippage will be only a few mm.

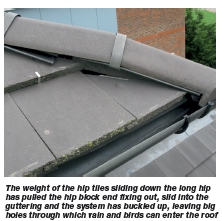

Where the hip tile fixing system is a plastic strap

that clips to the undertray, then there is the risk that the complete

hip line will slide down the undertray, compressing and taking up the

slack at every joint. The resulting hip slide can leave a gap at the

apex that may allow the hip ridge junction to fall apart, if it is not

screwed in place.

To prevent the line of hip tiles sliding off the roof,

the bottom hip block end is secured with a strong bracket to the hip

rafter with two screws. But if this fixing fails then there is no

secondary safety system.

If the block end is not clamped to the undertray

there is also the risk that the block end will buckle up around the

bracket under the force of the hip tiles above, leaving gaping holes and

the risk of further wind damage. To my knowledge there is no advice

provided regarding the maximum length of hip for any given rafter pitch

to guide specifiers, such that these pitfalls can be avoided.

Undertray

The undertray provides a level base for the hip tiles to sit on,

producing a straight and level hip line. Without the undertray the hip

line would dip and twist, especially with high profiled pan tiles.

With thin slates the line of the leading edges of the

slates are almost level from top to bottom. |

|

|

But with a profiled tile the cut may occur at any

point in the length or width which can vary enormously. As the tiles

either side of the hip will be cut differently this can result in

further variations in height from one side to the other. By having a

rigid undertray the hip line will crest just the high points in the

system. The undertray also acts as a water trough, or water shed for any

rain or snow, that may enter between the butt joints of the hip tiles,

to escape.

Below the undertray is the means of keeping out any

wind-driven rain. This can take the form of a fleece that is stretched

to the shape of the tile surface to maintain the shape, much like a

dressed lead flashing would do, or a vertical foam block wedged against

the cut edge of the tiles, or slates, to prevent water reaching the

underlay at that point. Whichever method is used, there is a physical

limit to the accuracy of the cut tiles and the amount of surface contact

of the fleece or foam block. In all cases the degree of surface contact

must be as much as possible and minimal contact is to be avoided as that

will be the point at which it will fail.

The cut tiles on a roof slope, especially at a shallow

rafter pitch, may be too small to reach the batten to allow a head

fixing. Even if the cut tile is nailed to a batten, there is always the

risk that the tile will rotate about the nib or nail fixing. Therefore

it is essential that the affected cut tiles are supported by a Z clip on

the leading edge, to prevent them falling out, or rotating. The Z clip

will vary in length with head-lap; therefore in most instances the clip

is bent on site. The bend must be at a right angle over the head of the

tile below to ensure that the clip can not slide out. Some manufacturers

recommend that double tiles are used when cutting tiles at a hip. This

method looks better but at shallow rafter pitches can still result in a

one nail head fixing and a rotating cut tile.

Conclusion

Dry hip systems work best on low pitch, light weight roof structures, on

flat interlocking tiles. As the pitch increases and the tile profile

gets deeper, so the suitability reduces. Each product manufacturer will

specify which tiles, pitch and plan angle their products can be used on

and at, but rarely mention other parameters such as rafter length or

other manufacturers’ tiles. Provided the fixing instructions are adhered

to, the dry hip system should perform as well as, or better than, a

mortar bedded hip.

Tips

- Secure all edge cuts with the clips provided and

an additional head nail where possible.

- Cut the edge tiles as parallel, and as close to

the hip rafter as possible.

- Do not leave any screw fixing, clip or other

fixing slack.

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|