|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

|

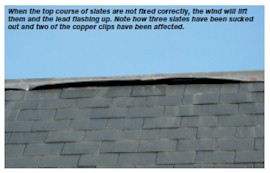

When I am asked to inspect or investigate

broken or slipped slates on a pitched roof, the most common problem that

I find is the top course of slates have not been installed correctly.

Most slaters think that what they have constructed is correct, but is

it?

First principles

To understand what should be done, we need to go back to the first

principles of how a slate on a pitched roof stays on, and what forces

try to remove it. Firstly we have weight, which pushes the slate onto

the surface of the batten but, because of the angle of the roof, may

also cause the slate to slip down the roof slope by the force of

gravity. To prevent this happening, the slates are nailed or hooked to

the battens.

There are two locations for nails: centre-nailing or

head-nailing. Head-nailing is normally undertaken with heavy and small

slates where the force of wind suction on the exposed surface of the

slate is insufficient to lift the slate. But with large, lightweight

slates, centre-nailing is used, as the nail position acts as a pivot –

which is more efficient – and the wind suction on the exposed surface of

the slate is resisted at the opposite end of the slate that rests on a

batten, turning uplift into downward force. Provided the slate is rigid,

this transfer of an upward force at the lower end to a downward force at

the top end should not bend or break the slate.

Types of slates and fixings

With fibre cement slates, which are thin and can flex in their length, a

copper disc rivet is used to transfer the majority of the wind upward

force on the exposed surface of the slate to the edges of the slates

below and into their centre-nail fixings. Therefore, provided the cut

course of slates that finish at a ridge or top edge abutment are

head-nailed and fixed with copper disc rivets at the tail, the wind

uplift forces will be resisted into the course of slates below.

With resin slates that are a bit thicker than

fibre cement slates, and will flex slightly less in their length, there

is no copper disc rivet fixing, so when the head of the slate is cut off

and the top slate is head-nailed, there is nothing but the weight of the

ridge tiles or the flashing to hold the slate down.

With natural slates, which are very rigid, once the

head of the slate is cut off, again there is nothing but the ridge tiles

or the flashing to hold the slates down against the wind uplift forces

on the exposed surface of the slate. Wind uplift forces on natural

slates that are fixed with slate hooks have their force resisted by the

slate hook through to the batten below and, therefore, when the heads of

the top slates are cut off, provided the slates are fixed with the slate

hooks, the slates will not lift.

Top edge detailing

We have seen that if a copper disc rivet is used at the tail of each top

slate this will hold the slate down, as will a slate hook, but to stop

the slates rotating about that fixing to the left or right, the top

slates also need to be head-nailed. But, where rivets or hooks are not

used, there are two other systems.

Firstly there is the shouldered method. This entails

cutting off the two top corners of the last full course of slates at 45°

to leave about half the width of the slate along the top edge. The

batten that is located under the top edge of the slate is positioned

about 25mm down from the top edge of the top of the slate so that it can

only be seen in the V-shaped spaces between the slates. The top course

of slates should now be cut such that the top edge finishes flush with

the top of the slate below. |

|

The only way the cut slate can be fixed is

to punch two new nail holes in the slate to coincide with the centre

line of the batten, as far apart as possible. The effect of moving the

batten down, and the top edge up, is to make it difficult for the cut

top course of slates to rotate about the new nail positions.

Secondly there is the double-batten method. With the

double-batten method, a second, larger batten is placed above and

against the head of the normal top batten. The thickness of the second

batten should be equal to, or a little more than, the thickness of the

batten plus the thickness of the slate, (normally 32mm). The top cut

course of slates are cut with the top edge level with the top edge of

the thicker batten. These cut slates are then twice nailed as normal

into the thinner top batten against the top edge of the course of slates

below. This means that between the nail and the top of the slate will be

about 75mm, which is sufficient to stop the slate rotating upwards. If

the second top batten is the same thickness as the other battens (25mm),

then the top slate will kick up, or can be lifted by the wind, until the

head of the slate meets the second batten face.

Ridge tiles and flashings

Some slaters and tilers believe that a mortar-bedded ridge or a lead

flashing is sufficient to hold a head-nailed top slate down. This is not

the case, as it is a bit like pulling a nail out with a claw hammer. The

exposed surface of the cut slate is usually much longer that the lap of

the ridge over the head of the slate so, in most instances, the slate

will lever up the ridge tile and break or crack the mortar bedding. Even

with dry-fix ridge systems, the ridge may not come off but can be

levered over to one side. With flashings, clipping the lead flashing

helps prevent the lead lifting, but is not strong enough to resist the

combined leverage of the top slate and the lead flashing.

Conclusion

Head-nailed slates such as stone slate should cope with being

head-nailed at a ridge or top edge, especially if they are nailed onto

rigid sarking. Fibre cement slates that are fixed with copper disc

rivets should not require additional fixings at a top edge, but

double-lap, centre-nailed slates should be either fixed with slate hooks

and nails, shouldered and nailed, or a second, larger batten should be

installed to stop the head of the slate from moving once it has been

twice nailed to the lower batten.

Tips

- Gauge out the roof and see where the

last course of slates finishes below the ridge or top edge before

deciding which method of additional fixing you will use, as

sometimes there is insufficient room to install the double batten

method.

- All ridge tiles should lap over the

top slate by a minimum of 75mm.

- In very windy locations, it may be

appropriate to use slate hooks and shoulder/double-batten the top

slates to fix them.

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|