|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

|

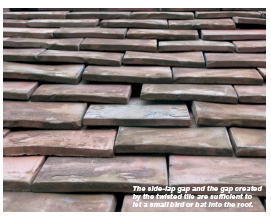

The first part of this article looked at

gaps and holes around a single lap tile. The second part looks at double

lap slates and tiles and a few general issues.

Slates

Slates, being thin rectangular sheets of stone, fibre cement, or resin

slate, are inherently simpler, and yet more sophisticated than tiles, as

the gaps between the surfaces are less controlled – especially with

stone slates that are rough/irregular, unlike most slates that are

smooth/regular.

If constructed correctly, all slates should lay

parallel with each other, and gaps between them should be sufficiently

small to allow a meniscus of water to build up between faces. The shape

of the meniscus will be different on the top surface of the slate than

it will be on the underside due to the double-lap arrangement.

Rough slates have less of a problem with water trapped

between the slates, while very smooth slates, like fibre cement, will

attract the most water. The larger the gaps between the slates, the more

air movement there will be between the slates, which helps to dry them

out quicker and reduces the risk of frost damage.

The more air that can be sucked between the slates, the

more wind uplift load is taken by the underlay, and the less load is

taken by the slate itself. Therefore, slates with gaps of two and three

millimetres between them will perform better in high winds than those

that are tight-fitting.

To prevent insects and bats entering the roof, the gaps

should not be more than 4mm. This also applies to side-laps, where the

slates are thicker than 4mm – side-lap gaps should not exceed 4mm. Where

the thickness of the slate is 4mm or less, the side-lap gaps can exceed

4mm.

But with fibre cement slates fixed with copper disc

rivets, the gap should not be less than 2mm, or greater than 9mm,

otherwise the copper disc will either not fit, or can pull through the

gap.

Slates in contact with each other will rub due to the

thermal movements of the roof. This will cause the surfaces of the slate

to abrade, resulting in a grey powder between the slates. While abrasion

will occur between all roofing materials, it appears to be more

noticeable with slates, as they are flatter.

With stone slates, which are very irregular, it was

traditional to back-bed them with lime mortar to prevent wind, birds and

insects gaining entry to the roof. In many instances, this has been

replaced with an unsightly mortar bedded joint, which prevents the

slates from breathing and locks them together, making them more

vulnerable to frost damage and breakage.

Plain tiles

Traditional double-camber plain tiles can have gaps between them of up

to 15mm high and 160mm wide, but, due to the steep pitch of the roof,

they do not suffer from water ingress. The camber in the width/length of

the tiles prevents water being trapped between the tiles. The gaps allow

air to circulate and keep the clay dry. Single camber clay tiles rely

upon a dense clay that will not absorb as much water, but unfortunately,

because air does not circulate between the tiles as easily as with

double-camber tiles, they do tend to deteriorate first on the underside.

With double-camber tiles, the large gaps will allow large

insects and small rodents to enter the batten cavity, and it is

therefore much more important to have a good underlay to prevent them

accessing the rest of the roof than with a single-camber tile.

|

|

|

The gaps can be reduced by using

cross-cambered tiles, which have a curved top and a straight bottom in

their width. This type is generally manufactured in concrete.

General

It has been observed that clay plain tiles and natural slates treated on

the underside with spray-applied polyurethane foam may suffer from

premature breakage, attributed to the gaps between the tiles being

filled with a material that prevents air from circulating around them,

so restricting the drying process and increasing the risk of frost

damage.

Also, the foam insulation locks together all the

elements and restricts the natural thermal movement of the tiles and

slates, which can result in the exposed section expanding in strong

sunlight and contracting in cold weather, and the foam embedded section

responding at a slower rate – causing stress in the material.

If a hole is drilled through the face of a tile or

slate, it should be replaced or, if the hole is for a very good reason,

it should be protected with a suitable material, such as a neoprene tap

washer under a screw head, or a suitable mastic or sealant around the

fitting/fixing to prevent any water seeping down the hole.

Wind-driven snow penetrates the smallest of gaps in a roof

covering. Because it is almost impossible to stop, it is essential to

have a good secondary roof covering of underlay that will collect the

snow and drain the melt water away into the eaves gutters.

Conclusion

Gaps and holes are a compromise. Spaces between tiles and slates need to

be big enough to allow air to circulate to reduce the risk of frost

damage, while not being too big to allow large insects and small bird

and animals to get into the roof. Meanwhile, the gaps should be as small

as possible to keep out the rain and the wind, but be big enough to let

water drain out and slow the wind down. Gaps are needed to allow the

system to function; sealing up, and locking together, roofing elements

will result in cracking and breakage of the slates or tiles.

Tips

- Small gaps between slates reduce the

effects of capillarity, and help to prevent water reaching the nail

holes.

- Double-camber plain tiles can resist

frost better than single-camber plain tiles.

- Wind-driven snow will penetrate even

the smallest gaps, requiring the underlay to catch the snow and

prevent it entering the roof.

- All gaps should be kept to less than

16mm to keep out small birds, and less than 4mm to keep out large

insects.

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|