|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

|

A good pitched roof will, over its lifetime,

be subjected to many thousands of gallons of rainwater, and never let

any of it pass onto the building below. But if you were to take the same

roof and turn it upside down and lower it into the sea, it would sink.

This may sound obvious, but it demonstrates that a

pitched roof is full of holes and gaps, through which water can flow but

water does not come in, as the roof covering is lapped in such a way as

to direct the water through and away from the gaps and holes. But, while

a roof is full of gaps and holes, what size of holes and gaps are

acceptable and unacceptable?

Between every slate and tile on a roof there are gaps,

either at the side or headlap. These gaps may be small and measured in

thousandths of a millimetre or large and measured in tens of

millimetres. Some are needed and others are not. Those that are needed

relate to water, wind and insect control; those that are unwanted are

generally caused by poor workmanship or defective materials.

Interlocking tiles

The whole reason for having a roof is to keep rain out, and this is done

by channelling water away from the edges and the top of each tile. With

modern, single-lap tiles, this is achieved using interlocks on the

surface and underside of the tile, where they meet.

The side interlocks are small gutters that collect the

rainwater and channel it away before it can spill off the edge of the

tile. For the gutter to work, it has to have a cross-section that allows

the maximum volume of water to flow down the channel, while at the same

time preventing water from seeping sideways by capillarity. As most

domestic roof slopes are no longer than 9m, most side interlock channels

are designed to cope with the maximum water run-off at the lowest pitch,

for the conditions typical once every 50 years anywhere in the UK.

The interlocks also need to keep out wind-driven rain and

debris such as pine needles and leaves.

Side interlocks generally have matching pairs of ribs

that lock one into the other, but the best arrangement is where one big

channel with a deep side and no corresponding upper rib allows the

maximum water capacity from top to bottom. At the bottom, the water

should have an unimpeded exit out onto the lower tile. For the sake of

appearance, we have tiles with thin leading edges with cut-back

interlocks that discharge the water into the headlap of the lower tile

and expect it to seep out through the headlap gaps. This works well

under average rainfall, but if the underside of the interlock rests on

the lower tile, water can be sucked back under the interlock and over

the head of the lower tile by capillarity, unless there is a device to

stop the capillarity (normally a groove that creates a gap).

Where two surfaces are within 1mm of each other, the

ability of water to travel up or across the tile between the surfaces is

made easier. But, by increasing the gap to 2mm or more, the water flow

is stopped. Large gaps can help to get water out of the side interlocks

and away before it can build up, especially if there is silt or debris

in the interlock channels, which can be a problem, especially at low

rafter pitches.

At the headlap, weather bars are designed into

the underside of the tile to prevent capillarity, and to slow down the

rain being driven in by the wind. Wind that passes through a narrow gap

and then enters the large void between the weather bars will slow down.

If this is done two or three times, the speed of the wind can be reduced

significantly. The amount of speed reduction is dependent on the minimum

gap size between the tiles and the maximum height of the weather bar

chamber.

|

|

Therefore, to achieve the maximum wind speed

reduction, the weather bars need to be close-fitting onto the lower

tile, and the voids between the weather bars need to be as deep and as

wide as possible.

If a tile is not laid correctly, kicking up around a

roof window, or sprocketed at the eaves, the close fit will be

compromised and therefore the weather bars will not perform efficiently,

if at all.

To provide sufficient space for both the side interlock channels

and the headlap weather bars, the tile needs to be approximately 25mm

thick.With clay interlocking tiles, the tolerances are harder to

maintain, so the width and depth of the channels and weather bars are

greater than for concrete tiles.

Ideally, the gaps along the outer edges where the

tiles abut another tile should be less than 1mm to achieve the maximum

performance. For tiles with a thin body depth, compromises have to be

made regarding the weather bar and interlock design. With resin slate,

this can be achieved through a high degree of accuracy and design.

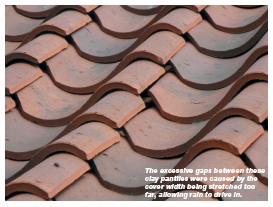

Traditional pantiles that have no interlocks and weather bars have to

rely on a steep (30°) rafter pitch to prevent wind-driven rain entering

the roof, and the large gaps to prevent capillarity.

If the gaps in the roof covering are larger than 4mm,

there is a high risk that large insects will get in between the tiles

and nest in the batten cavity. If the gaps are larger still, there is

the risk that bats, mice, birds, or squirrels will get into the roof. It

is for this reason that all dry-fix and ventilation components are

designed to have no gaps larger than 4mm. Traditionally, mortar has been

used to fill in all the known gaps around a roof, but there are places

where the gaps have always existed, and these should be restricted to

4mm maximum.

With high-profile pantiles and double Roman tiles, there has

always been a gap between the corrugation and the fascia board, through

which birds and rats can enter the roof from the gutters, and these

should be filled in with an eaves comb, or filler unit. The traditional

method was to lay a course of plain tiles and mortar the pantile onto

the plain tile undercloak.

When there were no eaves clips, this was the best

method available, but the fitting of eaves clips clashes with the plain

tile undercloak and should not be used together. Where more than one

course of plain tiles is used at the eaves the roof should be steeper

than 35°, otherwise the plain tiles will leak.

The second part of this article will deal with slates and

plain tiles and how gaps between double-lap products have a different

effect to single-lap tiles.Tips

- Interlocking tiles should all lay in

the same plane, with no tiles kicking up at the perimeters.

- There should be no gaps wider than

4mm between the tiles or the surrounding perimeter construction or

penetrations such as roof windows.

- Tiles with cut back interlocks look

neater, but can result in debris collecting and blocking the water

path from the side interlock.

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|