|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

It is generally accepted that lead lined inclined open valleys need to

be supported on substantial timber boards set between the rafters to

support the weight of the lead. However, with GRP valley trough units,

there has been conflicting recommendations regarding installation from

different manufacturers and suppliers. In recent years recommendations

have changed , but there are still some technical loose ends that need

to be resolved.Deflection

GRP is light and rigid and does not require supporting, unlike lead

which cannot support its own weight.

However, the forces acting on the unit are more than

just its self-weight. Inclined valleys are always laid at a shallower

pitch than the rafter pitch of the two adjacent slopes, by approximately

5°. This is the shallowest route from the eaves to the ridge and will

inevitably be used as a safe way to reach the ridge, especially if the

tiles or slates look fragile. While tradesmen on the roof may be

discouraged from walking up the valley, they will still be used as

walkways. Once a roof has been completed it is difficult to determine if

the valley trough is adequately supported. However, once you stand on it

and it deflects, it is too late. The weight of a tradesman standing on a

valley trough spanning between rafters will cause the GRP to deflect

sufficiently to stress-crack the material. Therefore, the construction

needs to be capable of supporting the weight of a man without excess

deflection.

Mortar

Valley trough units, used for interlocking tiles, have a sanding

strip along the edges of the open channel to allow the mortar bedding to

adhere to the surface of the material. In theory this works well.

However, if the valley trough unit deflects due to the point-load of a

tradesman standing on the valley, the mortar will not be able to bend

with the GRP, and will either crack or pull away from the sanded strip.

Neither option is desirable. The only way mortar bedding will remain in

position is for the valley trough to be supported so that there is

little or no deflection.

Battens

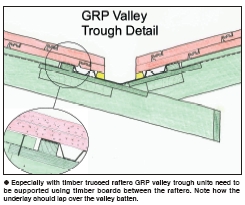

At an open valley the tile or slate battens need to terminate short of the

centre-line of the valley. This allows the valley trough to sit in the

depth of the batten and not kick up the edge tiles or slates. This will

result in some batten ends being unsupported, unless there is a board

that is set between the rafters, or a valley batten to which to fix

them. The end of every batten should be supported by being nailed to a

timber support. In many instances the timber support boards, if wide

enough, will serve as a suitable support.

The alternative method of mitre-cutting the end of the

batten to the side of the valley batten, and then tosh-nailing up

through thin edge of the tile batten into the valley batten, is not

discouraged, but is clearly not as secure. Nailing through the thin edge

of the batten so close to the end grain of the batten will inevitably

split the batten when using a standard batten nail. This method of

securing the ends of the battens also alters the detailing of the

underlay.

Underlay

If there are no support boards under

the valley trough units the underlay will sag between the rafters. It

will only come into contact with the valley trough units where the

underlay passes over a rafter or down the valley rafter. If there is no

valley rafter, as with trussed rafter roofs, the expansion and

contraction of the valley trough units will eventually wear through the

underlay on the edges of the timbers. If water on the roof underlay is

allowed to drain under the valley it can drain through the holes worn in

the underlay.

|

|

Underlay that is laid on a relatively smooth

support board is less likely to wear through as the movement takes place

over a much greater surface area. Similarly, bituminous underlay can

become adhered to the underside of the valley trough after periods of

hot weather.

The contraction of the GRP in cold weather can tear the

underlay apart at the laps in the valley trough units. It is, therefore,

ideal if the underlay under the valley is not bituminous and is laid

over the valley battens along with the main roof slope underlay. This

will prevent water on the main roof slope underlay from draining under

the valley. A 10mm gap is needed between the end of the tile battens and

the side of the valley batten. This will encourage water on the main

roof slope underlay to drain down the side of the valley batten. This

makes the nailing of the battens into the valley batten impossible.

Valley trough profiles

There are three generic profiles of GRP valley trough, not including the

proprietary dry valley designs. These are troughs that need a valley

batten to support the outer edges, those that do not, those designed for

interlocking tiles with mortar, and those designed for double lap slates

with no mortar.

There are also two widths of trough. It is not clear

when, or why, you would choose one design over another. The wider units

provide a wider clear open channel down the centre, and in some

instances, larger corrugations to channel any water that may get through

the mortar bedding. It is also recognised that troughs that finish on

the top of a valley batten are more weather resistant at lower rafter

pitches than those that finish at rafter level and do not need a valley

batten to support the edge.

The recommendation states that units that do not need a

valley batten are designed for used with rigid sarking. Where a counter

batten is used, I see no reason why valley trough units that need a

valley batten should not be used with rigid sarking applications. It is

also not clear as to which units are used for plain tiles. While they

are double lapped like natural slates, the thickness of the tiles at

approximately 13mm is large enough to allow insects into the batten

cavity. Therefore, it would be better to mortar bed plain tiles at a

valley.

Conclusion

The suggestion that no support or

partial support, with 6mm sheets of ply-wood, below GRP valley trough

units is acceptable, is less than helpful as they will be liable to fail

in the long term. Full support of the valley trough units using a 19mm

timber, or a 15mm plywood support board, set between the rafters and

wider than the valley, with a non bitumen underlay under the valley, is

the only safe option.

Tips

- The end 50mm of all battens should be

supported and fixed to the valley support board

- The underlay under the valley should

ideally not be bituminous

- Water on the main roof slope underlay

should not be allowed to drain under a valley by lapping it over the

valley battens

|

| Compiled by Chris Thomas, The Tiled

Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove, Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey,

RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|