|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

Most materials such as steel, timber, or

plastic, if placed under load will bend before they break. Whilst

materials such as concrete or rock do bend under load, they are more

likely to break before bending can be seen in a small component like a

slate.

With best quality natural slate, the maximum

uplift wind force expected once in 50 years in the UK, acting on the

exposed surface of the slate, is unlikely to generate any measurable

bending through its length. That is unless the slate is too thin or

faulty, then the slate will snap at its weakest point.

A fibre cement slate that is 4mm thick will

bend under wind loads and thermal stress and therefore needs some

assistance to resist the bending forces. This is achieved with a copper

tail rivet, positioned in the centre of the slate close to the leading

edge, to clamp the top slate to the two lower slates. This little device

- like an upturned mushroom - is slid up in the gap between the lower

slates and located through a pre punched hole in the top slate, and the

pin is bent over to lock the slates and the rivet together.

The majority of the wind uplift load on the

exposed section of the slate is transferred to the copper tail rivet.

The load in turn transfers to the edges of the two slates below, which

in turn transfers the load to the two centre fix nails of the lower

slates.

To stop the rivet pulling up through the gap

between the slates, British Standard 5534 recommends that the gap should

not be wider than 5mm, when using a Copper tail rivet with a base

diameter of 19mm. At best, 7mm to 8.5mm of the disc will lay under each

of the lower slates. However, if the setting out of the slates is less

than perfect the rivet pin could lay to one side, making the lap under

the other slate as little as 5.5 mm. If the slates are laid with gaps

between 5mm and 9mm, the risk of the rivet pulling through the gap

increases. When the slate gap is 10mm, and the rivet pin is not central,

the lap under one of the slates can be as little as 0.5mm and the force

needed to pull the rivet through the gap negligible. If the rivet can

pull up on one side, it can rotate and completely detach from the lower

slates.

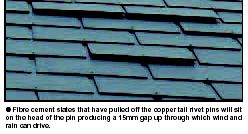

Another mode of failure can occur if the rivet pin is either not bent

over at right angles onto the top surface of the top slate, or is not

long enough and therefore cannot be bent over far enough to clear the

hole in the slate. In both instances the uplift force required to either

straighten the rivet pin or damage the hole in the slate and allow the

rivet pin to pull through can be within the limits of normal wind force.

Once the uplift force on the slates has bent the rivet pin to 45° from

the vertical, the slate can lift off the pin under wind suction and not

relocate onto the pin, but will sit on the head of the pin and show

itself as a lifted slate. If left the rivet can vibrate down the gap

between the slates and the slate will drop back into position, but

without a tail rivet fixing.

|

|

| The hole in the

slate for the copper tail rivet should be slightly larger than the

2mm-diameter rivet pin. Too large and the length of

the rivet pin will need to be increased to stop it pulling through after

it has been bent over. The position of the hole back from the leading

edge is also critical. Too close to the leading edge and it will weaken

the edge of the slate and break away under load. Too far away and the

efficiency of the fixing will be reduced. The length of the pin should

protrude approximately 10mm above the slate before it is bent over. With

most FC slates being approximately 4mm thick this should not be a

problem, but if thicker slates are used, the pin on the rivet needs to

be equal to two thickness of slate +10 mm.

Some roofers have been known to once nail and

tail rivet some slates on a roof. After a short time, each once nailed

slate rotates about the nail fixing and closes the gap between the slate

on one side and opens up the gap on the other, making the grip of the

tail rivet less than it should be. Also with the slate being held down

only on one side, the other side is able to lift allowing the tail rivet

in some instances to fall out.

The worst case is where isolated slates have been broken during

construction and new slates inserted. As it is impossible to re-nail the

new slate into position, the tail rivet is used as the only means of

fixing. This is totally unacceptable, as over time the slate will slide

down the roof until the rivet disengages with the lower slates, and then

is blown off or continues to slide.

- Twice nailing and tail riveting FC

slates is a very efficient system provided the slates are set out

with gaps up to 5mm wide and the copper tail rivets are installed

correctly.

- Setting out should be carefully

controlled to ensure the perp lines do not drift and upset the

spacing of the slates.

- All slates must be twice nailed and

tail riveted or fixed using proprietary slate fixings.

- All copper tail rivet pins should be

long enough and be bent over at right angles onto the top surface of

the slate.

|

| Compiled by Chris Thomas, The Tiled

Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove, Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey,

RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|