During the hurricane force winds of 1987

and 1990, the most common form of roof damage was the loss of end ridge

tiles. Until the high winds struck, the ridge tiles had sat in place

under their own self-weight. But once wind suction became greater than

the self-weight of the ridge tile, they became objects of further

destruction, bouncing down the roof and breaking more roof tiles or

slates.

When the ridge tiles were originally laid in

mortar, the bedding may have been adequate. But over the years movement

in the roof caused the bond between the mortar and the ridge tile, or

the roof tile, to crack, leaving no bond or mechanical fixing to help

the tiles resist wind suction forces.

Differential movement

All materials will expand or contract when heated or cooled. Some

materials will also expand and contract with moisture content, such as

timber. It can be calculated that a timber trussed rafter roof will, on

average, rise and fall by approximately 40mm more than the brick and

block gable end walls, between the warm wet and cold dry times of year.

This difference in movement places more stress on the end ridge tiles

than others along the ridgeline. The result is a greater risk of end

ridge mortar failure.

In response to this form of failure, British

Standard 5534, The code of practice for slating and tiling: Design 1997,

stipulates that the end 900mm of ridge tiles should be mechanically

fixed. This also applies to where a ridge passes over an intermediate

wall or against a solid abutment. There are various end ridge-fixing

methods, of which the most secure solution is screwing the end ridge

tiles to the roof structure.

Mechanical fixings

To fix an end ridge tile correctly, the ridge board or a ridge

batten must extend to within 100mm of the verge edge and be a minimum of

38mm wide. The ridge board and batten need to be high enough to allow

the screw fixing to penetrate the timber by at least 40mm. Any ridge

batten should be fixed to the roof structure with holding down straps or

screws, not nails, as they could pull out under load.

|

|

|

The ridge tile should be neatly drilled in

the centre to allow the fixing to pass through into the ridge batten or

board below. The best fixing would be a dome head

stainless steel screw with a neoprene washer and a shaped plate to match

the apex of the ridge. The washer should seal the hole in the plate to

stop water tracking down it and the plate to spread the load out over

the ridge tile for an area of approximately 50 by 50mm. A screw can be

tightened down with little disturbance to the mortar; however a nail of

the same size will need to be hammered in, disturbing the mortar and

leaving the head clear of the plate. The use of wires is not very

satisfactory, as it is only possible to secure one end of the ridge.

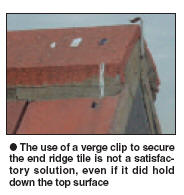

Dry fix ridge systems

The end ridge of a dry fixed ridge also needs to be secured. Most

dry fixed ridge systems have straps or plates at the joint between the

ridge tiles to hold down the two edges. At a gable end there is no joint

resulting in only one end being held down. The recommended end ridge

fixing for a dry fixed ridge is to use a block end ridge tile with an

additional fixing hole and screw, or the use of a plastics end cap

nailed into the end grain of the ridge board or batten. If the dry ridge

finishes onto a mortar bedded verge without a block end ridge or end

cap, it should be fixed as if it were a mortar bedded ridge.

The secure fixing of all end ridge tiles as

recommended by BS 5534 should help to reduce future insurance claims and

thereby help to reduce all associated insurance premiums

|

| Compiled by Chris Thomas, The Tiled

Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove, Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey,

RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |