| Natural slates by their very nature are simple

thin slabs or rock held onto the roof with two nails. What could be

simpler than that? But for the system to work the slates need to be rigid

in their length and width, and the nail fixings need to perform their

function of holding the slate tightly to the roof structure. The best

technique is to use centre nailing. But this alone is not without its

problems. |

|

Centre Nailing |

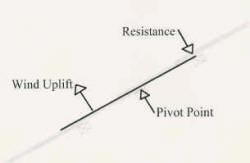

| The centre nailing of double lap natural or resin slates is a very

efficient method of securing slates to a roof structure. With the upper

part of the slate resting on one batten and the middle of the slate nailed

through into another slate, wind suction on the lower exposed section of

slate tries to rotate upwards about the centre nail fixings. The upward

lift of the lower half of the slate forces the upper part of the slate

onto the top batten. |

|

| As the uplift force

of the lower exposed section of the slate increases, the inability to rotate

about the nail fixings forces the slate to try and rotate about the top edge

of the slate. |

| To do this the slate needs to pull the centre

nails out of the lower batten. The further the nail fixings are away from

the top of the slate, the greater will be the lever arm effect of the

fixings. A typical twice nailed 30x3.0mm copper nail fixing with 500x250mm

slates can by calculation be expected to resist the anticipated wind

forces for all but the most exposed roofs in the UK. |

|

Raised Nail Fixings |

| The correct way of nailing a slate into position is to drive the nail

fully down into the timber batten, such that the head of the nail is

located in the spalled cup of the nail hole, or is in contact with the

surface of the slate. Most slaters will drive the nail down to within

0.5mm of the surface of the slate for fear of hitting the slate and

breaking it. This will allow the leading edge of the slate to lift up to

about 1mm. |

|

| The

greater the distance between the underside of the nail head and the top of

the slate, the more the leading edge of the slate can be lifted by the wind.

The more the leading edge can be lifted the greater the risk of the wind

causing the slates to rattle, making a lot of noise. |

| Also as the wind lifts a slate it can stop with

a jolt, placing a greater stress on the slate at the nail hole position,

causing the slate to snap between the nail hole fixings. |

|

Resin Slate Camber |

| Nail heads with more than 2mm below them will also hold the next slate

up clear of the slate below. The larger the nail gap the greater the gaps

between the slates will be. With Natural slates the gapping will not only

allow wind driven rain to enter the head-lap, but will also result in

breakage of the slate if walked on as the nail heads act as point supports

for the load, increasing the stress. With resin slates raised nail gapping

will increase during the first five years as the material relaxes. |

|

| Resin slates begin

life with a slight camber in their length. Whilst being nailed the slate

must be pushed down onto the lower slate and the nails driven fully home. |

| If this is not done a gap will be left between the slates.

With time the memory in the material causes it to relax back into a flat

sheet. The material will continue to relax until it rests on the lower

slate and the raised nail heads of the course below. This can result in

the slate developing a camber in the opposite direction, causing the

leading edge to lift more excessively. |

|

Batten Bounce |

| The reason for the existence of raised nails

may be craftsman's error, but it may not be! It may be that it is

impossible to drive the nail into the batten any further. Springy battens

can allow batten bounce to occur. This is when a batten acts like a leaf

spring. It is most common at the mid span position of rafters at 600mm centres,

close to a verge or side abutment and with sub-standard battens. The

impact load of the hammer hitting the nail head should force the nail into

the timber batten, but some of the force will also cause the batten to

deflect. The larger the nail diameter and the greater the nail penetration

into the batten, the more force that is needed to drive it in. There comes

a point where the force needed to drive the nail into the batten is more

than to deflect the batten or bend the nail. At this point it is

impossible to drive the nail in any further. The consequences of batten

bounce are that at maximum penetration the nail may be 3-4mm above the

slate, but under maximum impact the batten may deflect more than 3-4mm.

The slate being flat and rigid will not follow the curve of the batten and

will span across the curve. When the gap below the nail hole becomes more

than 3-4mm the nail head will come into contact with the slate and stress

the slate at that point, resulting in breakage. In this situation it may

be better to remove the nail and screw the slate into position, as a screw

will pull the batten up with no deflection. |

| Expansion and contraction, or wetting and

drying, of the timber do not cause raised nails. Research has found that

the only way a nail will come out of timber is with a tensile load, i.e.

it is pulled out by a greater force than the grip resistance of the nail

in the timber. If nails did work their way out due to thermal or moisture

effects, we would have an epidemic of loose tile and slate battens, which

is just not reality. |

|

Nail Holes |

| The position of the nail hole relative to the

edge of the slate is critical. The closer the nail hole is to the edge of

the slate the greater the risk of having a badly formed nail hole or

breakage of the edge of the slate. The nail hole should not be any closer

than 20mm in from the edge of the slate and not so far in that it comes

within the area of the slate potentially affected by water penetration.

The actual maximum distance in from the edge will vary with slate width,

head-lap and rafter pitch (further guidance is given in BS5534) |

| The size of the nail hole can sometimes be too large for the

head of the nail, with only a small part of the nail head coming into

contact with the surface of the slate, thereby reducing its effectiveness

in transferring the wind uplift load into the batten. Wherever possible

the nail hole should be slightly larger (1mm) than the diameter of the

nail and be punched from the rear to leave a slight dish on the face to

allow the nail head to sit into the slate. If the first nail hole is

defective there may be room for a second nail hole along the batten line

before it falls too close to the edge or the potential area affected by

water penetration close to the centre of the slate. |

|

|

Re-fixing slates with nails or screws

can only be achieved if a patch of slates is removed or re-slating back up

to the ridge is undertaken. |

|

Conclusion |

| Nails are a very simple and effective method of

securing slates to a roof, but they must be installed correctly, both in

terms of the head being in close proximity to the slate, and the slate

being in close proximity to the batten. The slate needs to be rigid,

strong and have clean nail holes punched in the correct location for the

fixings. What could be simpler? |